Lazzaro Felice: The Saint Among Us

Like the symbolism of spring, biblical figure, Lazarus, is another ode to rebirth, hope, and miracles. On the silver screen, director and writer Alice Rohrwacher brought to life a neorealistic, dreamy rendition of the tale of Lazarus woven into Italian folklore with Lazzaro Felice (2018). Starring Adriano Tardiolo as Lazzaro, the story revolves around a young, innocent, pure-spirited Lazzaro who lives life as a sharecropper for the de Luna family in small-town Inviolata until he meets the marquise de Luna’s son, Tancredi (played by Luca Chikovani as the younger version of Tancredi, Tommaso Ragno as the older version of Tancredi), forever altering the course of his life. With Rohrwacher’s fifth feature film, she brought this Italian artwork to the big stage during the Cannes Film Festival in 2018, even scoring the Prix du Scénario (Best Screenplay Award). The film explores exploitation as a cycle and selflessness via a Super 16mm format through the lens of director of photography (D.P.) Hélène Louvart.

∙

∙

We are introduced to one big found family of tobacco sharecroppers employed under the “Cigarette Queen”, Marchesa Alfonsina de Luna (played by Nicoletta Braschi). Sharecropping has been declared illegal in Italy, but the news has not reached the workers of remote Inviolata. Despite working through harsh conditions, the sharecroppers make sure that young, fellow Lazzaro remains at their disposal for any and all tasks. On the other side of the coin, the de Luna family is well aware of the crimes they are committing to fuel their noble lifestyle. The marquise’s son, Tancredi, who has developed a bad smoking habit (shocker!), turns his nose up and decides he wants nothing to do with this lifestyle anymore. Running away to Lazzaro’s small cave escape in the hills, Tancredi decides to befriend the pure-hearted boy. Fast forward, even years down the line after the sharecroppers broke free of the inhumane life they were living, we see that some of them, notably, Antonia (played by Alba Rohrwacher as the older Antonia) and her family, continue to fool everyday people by selling fake trinkets and constructing falsified sob stories for money. No matter what, the people Lazzaro valued as important used him time after time. And time after time he obliged to their will.

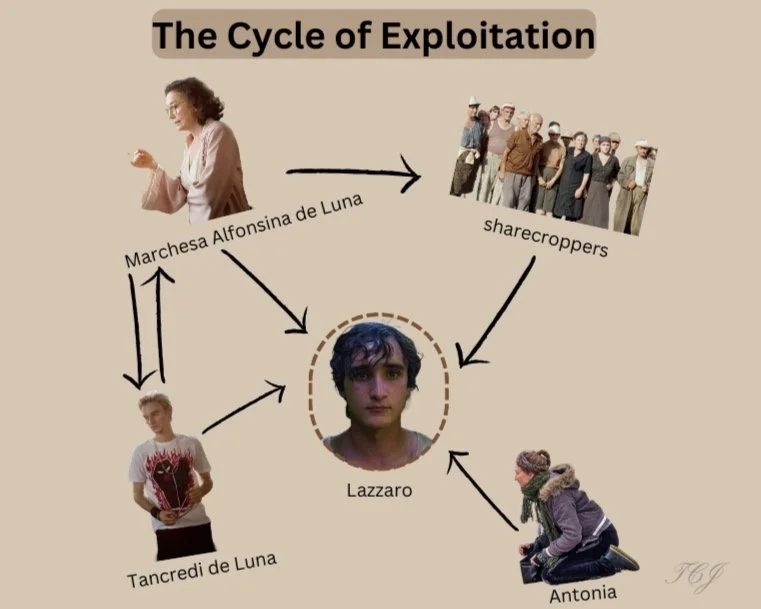

The marquise exploits the sharecroppers for free labor, the sharecroppers exploit Lazzaro for his willingness to help, Tancredi exploits Lazzaro and his mother in order to fake his kidnapping and for ransom money, the marquise exploits her own son as well as other smokers to fuel her cigarette business. Exploitation is a cycle that remains unbroken. And when it comes to those who are selfless, who have known nothing in life but to have a good heart, are left in that cycle of exploitation.

“I exploit them, they exploit that poor man. It’s a chain reaction that can’t be stopped”

— Marchesa Alfonsina de Luna, Lazzaro Felice (2018)

∙

∙

Throughout the film, we hear the narration of ancient folklore surrounding a wolf that has been pursued by townspeople with no avail. One day, the wolf discovers a man sprawled on nature’s floor and prepares to eat him. But, the wolf realizes that the man has the “smell of a good man”, which was very rare to come by. This folk tale is important because it is exactly what our protagonist experiences. Lazzaro is a default-of-ill-will, almost annoyingly naïve young man and remains so for the rest of his life. Even after he accidentally falls off of a cliff and loses his life. The feared wolf examined Lazzaro’s body and spares him. Just like Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead, the wolf granted Lazzaro a second chance at life because it caught the "smell of a good man”. If anyone is a textbook-good-person, it’s Lazzaro. People like him don’t exist in this day and age anymore, which has made others more greedy to use him for their liking. The only other emotion that we see in our Happy Lazzaro is his singular tear at the end of the film when he finally understood the betrayal he has known since the beginning. Almost bringing about a consciousness to him.

Shooting dreamlike sequences with hard-hitting underlying themes is one of Alice Rohrwacher’s strong suits. Much of this is in credit to D.P. Hélène Louvart, the French cinematographer that has accompanied Rohrwacher on much of her projects. What I understood as most profound is her use of the Kodak Vision 3 250D for daytime shots and Kodak Vision 3 500T for nighttime shots. As Louvart told Cinematography World, the daytime shots depicted the “harsh summer sunshine” and downtrodden conditions the sharecroppers endured in contrast to the nighttime’s “dark and under-exposed” scenery. Using different types of camera to evoke different emotions and thoughts is symbolic of a dedicated filmmaker. Being shot on film rather than digital in the modern day is vital because the storyteller swaps the artificial, inorganic lens with a more raw, true-to-life one. Changing some settings on a digital camera is very easy, but transforming the environment your film camera captures to convey a message is real filmmaking. Through the realism of the Super 16mm film, the audience is able to fully immerse themselves in the world of the sharecroppers and Lazzaro. I really hope to see more of Rohrwacher and Louvart’s work in tandem.

Lazzaro Felice (2018) is a phenomenal, eye-opening depiction of the human experience in a world where good and bad intertwine with one another to just make it to another day. Symbolic of the everyday life you and I lead, it brings the question…is there a saint dwelling amongst us, bending to our will? Who is our Lazzaro?